| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Aarhus |

| Vessel Type | Iron sailing, barque |

| Year Built | 1875 |

| Location Built | Hamburg, Germany |

| Dimensions | Length: 170 ft, Width: 28.3 ft, Depth: 17.6 ft |

| Tonnage | 640 tons |

| Departure Port | New York, USA |

| Destination Port | Brisbane, Australia |

| Date of Wreck | 24 February 1894 |

| Wreck Location | Smith Rock (off Cape Moreton), Queensland |

| Coordinates (approx.) | -27.0023849905 153.437984915 |

| Cause of Wreck | Struck Smith Rock while waiting for pilot |

| Survivors | All crew (14), captain, and captain’s wife survived |

| Depth (Max / Avg) | 21 m / 18 m |

| Protected Zone Radius | 500 m (permit required to dive) |

| Marine Life | Sponges, corals, reef fish, rays, octopus, wobbegongs |

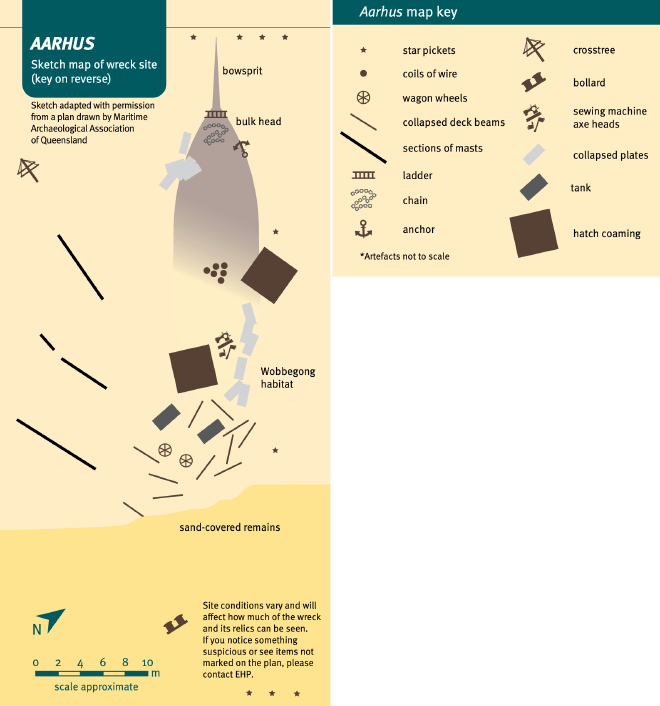

| Artefacts at Site | Bowsprit, anchors, deck plating, wire bales, collapsed stern, starboard bow section |

Part 1 - Summary #

The Wreck of the Aarhus: A Collision of Caution and Rock #

On a humid Brisbane morning the Marine Board chamber filled with Captain Almond, Hon. F. H. Hart, J. D. Campbell, Hon. E. B. Forrest and Captain R. S. Taylor, Danish Consul A. R. H. Pietzcker and barrister A. Leeper assembled to discuss the loss of the iron barque Aarhus1. Before proceedings began, the first mate was asked to step outside, leaving just the guide pilot, lighthouse keeper, coxswain, and Captain Christian N. Gram1.

Gram had commanded the 170-foot, 640-ton vessel—built of riveted iron and registered in Denmark, since before her papers and hull vanished beneath him1 2. Laid down in Hamburg in 1874–75 as Thalassa and sold to Danish merchant J. Hansen Christiansen of Nordby in December 1890, she became Aarhus and ran profitable routes from Sydney to Venice and Livorno before loading in New York2. Late in 1893 she cleared that port with a £15,000 cargo of kerosene, plaster, resin, dress fabrics, sewing machines, carriage wheels, reels of wire and 981 packages of general merchandise for Brisbane after a 122-day passage2.

The complete cargo manifest2:

| 16,200 cases of kerosene | 50 cases of canned goods |

| 30 cases of axle grease | 17 cases of scales |

| 200 barrels of resin | 44 packages of casings |

| 41 packages of kalsomine | 11 cases of agricultural implements |

| 4 packages of dress | 81 cases of axes |

| 400 reels of wire goods | 11 packages of ploughs |

| 825 boxes of cloth pins | 24 cases of books |

| 4 packages of stationary | 6 cases of picture frames |

| 9 cases of varnish | 20 cases of sewing machines |

| 90 packages of carriage wheels | 3 bundles of shoe dressing |

| 16 bales of dry goods | 22 cases of pumps |

| 31 bundles of shoe pegs | 981 packages of general merchandise |

| 69 cases of oil clothing | 61 bales of paper |

| 40 cases of fruit juice | 8 packages of churns |

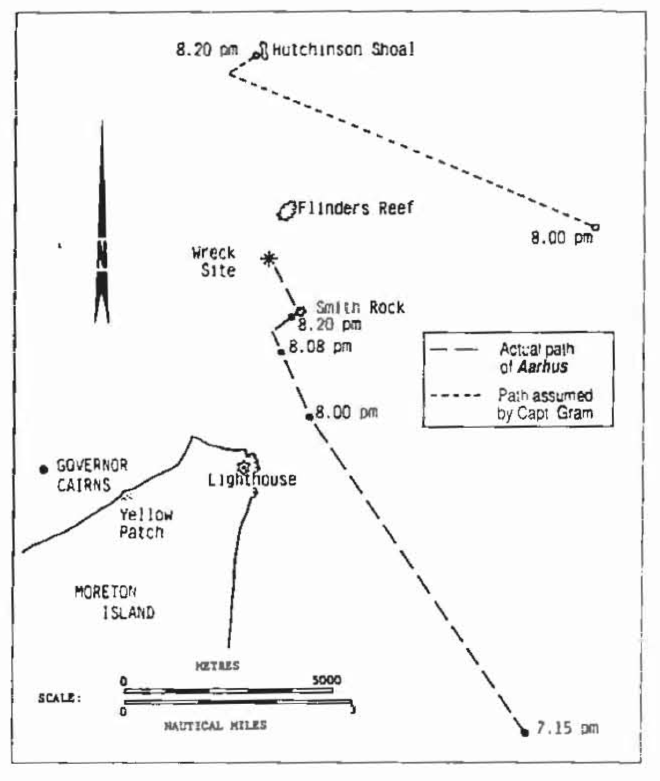

At dusk on 24 February 1894, making five knots on a north-half-west heading 10-15 miles, or so Gram believed, off Cape Moreton, the barque answered a 7.15 p.m. blue-light from the lighthouse and, 45 minutes later, another from the pilot schooner Governor Cairns glimmering off her starboard quarter1 2. Budget cuts had retired the steam launch Advance, and the aging Governor Cairns now seldom ventured beyond a bureaucratic line between Yellow Patch and Flinders Reef, forcing inbound captains dangerously close to shoal water2. Using only a three-year-old Hamburg coastal chart and Findlay’s South Pacific Directory, whose pages warned of Smith Rock yet promised pilotage, and with haze ruining his noon sight, Gram hauled the main-yard, put the helm NNE and 1/4E, and took bearings: Cape Moreton SW and 1/2W at six miles, then S by W 1/2E at seven, while waiting for a pilot who never came1. In reality Aarhus was barely a mile from the reef, and the south-south-easterly airs pressed her hard on a starboard tack toward Smith Rock2. At 8.20 p.m. her keel hammered the rock three times with such force that a foot of water surged into the hold1 2.

Gram tried to claw off, but each impact was worse than the last, and he ordered 12 rockets fired and a lantern hoisted while the crew hauled starboard boats to the weather side1. Heavy swell swamped the larger cutter, and five minutes later the sounding pipe spouted as the deck went under1. Within roughly 12 minutes of the first strike on the rocks, the fully rigged Aarhus slid stern-first under a moderate swell into 12 fathoms of water1 2. Gram, his wife, and thirteen crew rowed toward Yellow Patch Light, reached it at about 11 p.m., received directions from the keeper, and finally made it ashore on Moreton Island two hours after the wreck1 2.

Interrogated next morning, Gram conceded he carried no large-scale harbour chart and had relied on fleeting glimpses of Mount Tempest and Cape Moreton, convinced the pilot would board him1. The pilot schooner’s crew later admitted they had remained aboard until rockets burst overhead, a delay that Gram said sealed his fate because he never saw their lantern on the water1. Pilot Blanchard countered that custom required an inbound vessel to close with the pilot once a flare was acknowledged, claiming Gram’s hesitation had driven the barque into unseen danger1. The Marine Board ultimately rebuked Gram for navigational errors yet excoriated the pilot service for the “sluggishness of movement” born of chronic underfunding2. Gram left Brisbane before the verdict was handed down and was later vindicated when the Nordby Maritime Court in Denmark placed legal responsibility squarely on Queensland’s pilot authority, noting regulations that told masters to wait where no pilot now ventured2.

Salvors bought the wreck at auction, yet diver George May soon reported only a shattered hull and battered kerosene tins rolling in the surge2. The masts were dynamited in 1919 as a hazard to navigation, and even the green wreck buoy that once marked the spot disappeared over time2. Aarhus faded from public memory until volunteers from the Underwater Research Group of Queensland began manta-board surveys between 1975 and 1978, combing seabed 1.5 kilometres off the 1880 charted position2. A visiting US-Navy helicopter magnetometer fixed the coordinates, allowing filmmaker Ben Cropp to log the first modern dive in calm seas in 19782. URGQ teams relocated the site again in 1981, and it was immediately protected under the Historic Shipwrecks Act with a 500-metre exclusion zone2.

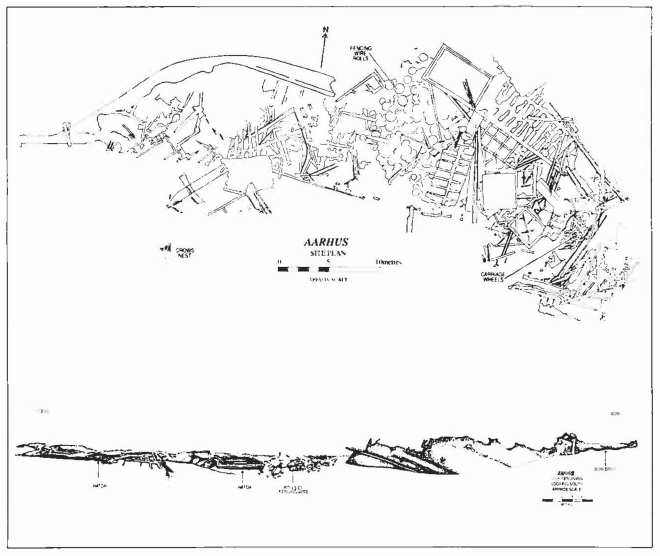

Since 1984 the Maritime Archaeological Association of Queensland has treated Aarhus as an underwater classroom, laying a 60-metre stainless-steel baseline along her starboard flank, pegging grid lines with a yabbie-pump water-jet and stitching a photomosaic of the site2. The hull rests just east of Cape Moreton on its starboard side in 21 metres of water, bow pointing west, amid coils of fencing wire and elegant carriage wheels—mute reminders of Queensland’s frontier economy2. Corals, sponges and schooling fish now cover the iron wreck, and plans to chart sediment movement and probe the buried stern have stalled more than once when six-metre southerly seas slam across Smith Rock2.

From her Hamburg forge to her rust-reefed Queensland grave, Aarhus embodies colonial trade, bureaucratic complacency, human error and scientific curiosity, a saga the sea continues to tell each time divers descend through restless water above Smith Rock1 2.

Today: The Aarhus Beneath the Waves #

Now lying 21 metres beneath the sea near Smith Rock, the wreck of the Aarhus has become a protected time capsule3. Partially buried in sand, her collapsed stern, massive anchors, coils of coral-encrusted wire, and even sewing machines remain scattered across the seabed — silent witnesses to a maritime miscalculation.

The site teems with life. Wobbegong sharks nestle beneath rusting beams. Reef fish, rays, and curious octopuses swirl through the twisted wreckage. For experienced divers granted permit access, the Aarhus offers a haunting dive into Queensland’s maritime history3.

But tread lightly — this is not just a dive site. It’s an underwater museum, a ship lost not to storm or fire, but to the shadowy edge of human error.

Photos: 2011 Brisbane Times4 and Undersea Productions5.

Part 2 - Research #

News Articles & Media #

02 March 1894 - The Brisbane Courier - The Wreck of the Aarhus #

The following article was from Trove’s archives1.

THE WRECK OF THE AARHUS. MARINE BOARD INQUIRY. The Marine Board inquiry into the circum- stances attending the wreck of the Aarhus on Smith’s Rock was commenced yesterday, before Captain Almond (chairman), Hon. F. H. Hart, Mr. J. D. Campbell, Hon. E. B. Forrest, and Captain R. S. Taylor. Mr. A. R. H. Pietzcker, the Danish Consul, was also present. Mr. A. LEEPER (instructed by Mossrs. Un- mack and Fox) appeared for the captain. Before the proceedings were commenoed he asked that the witnesses should be ordered out of court.

Captain ALMOND explained that the pilot, the lighthouse keeper, and the coxswain were pre- sent as defendants, and could not, therefore, bo asked to retire. He directed, however, that the first mate of the Aarhus should withdraw.

Christian N. Gram stated that he was captain of the barque Aarhusch was an iron vessel of 640 tons, Danish register. Ho had a certificate of competency as master, but it had been lost with the ship. At 7.15 p.m. on the 24th February the ship was ten or fifteen miles from land on her beam, steering N.1/2 W. The vessel was sailing at about five miles an hour. He showed a blue light, which was answered from the Cape Moreton Lighthouse almost at once. At 8 o’clock he showed another blue light, which was answered from the pilot cutter. He had the mainyard put to the mast, all the other sails being full, and put the ship N.N.E., with a quarter of a point east in deviation. Soon afterwards he saw a second light from the pilot vessel. About five minutes afterwards Cape Moreton was S.W.1/2.W., with half-a-point east deviation, distant six miles. Eight minutes afterwards they had the Cape S. by W. 1/2.E., distant from six to seven miles. At the same time they saw a flare-up from the pilot vessel. He gave the mate instructions to fill the mainyard and put on all sail, and the man at the wheel to steer out by the wind. The wind was about south-south-east, perhaps a little easterly or south-east by south. The vessel was then lying south-east by east. The yards were braced up on the starboard tack. As they were setting the foresail the ship struck. He did not take her bearing. She struck so hard that it seemed as if the whole of the rigging would come down upon them. The vessel had not been brought to the wind. When they saw that the pilot was not coming he decided to stand out to sea again, and it was while he was attempting to do this that the vessel struck. The well was sounded at once, and there was 1ft. of water in the hold. He ordered two boats to be cleared. Twelve rockets were sent up and a light burned on the port quarter at the fore part of the poop. The starboard boats were at once set out on the port side, there being too much sea to enable the other side to be used, At that time the vessel struck a second or third time, and the mate taking the soundings found a depth of thirteen fathoms. The port boats were lowered from amidships on the port side, but filled with water. The small boat was bailed out, but there was no time to bail out the big boat. Five minutes after the sounding of the pumps the water began to come up the sounding-pipe on to the deck. He thought they struck at from twenty minutes to thirty minutes past 8 o’olook. He ordered all to take to the boats, and everyone having left they rowed away from the ship, as the water rose a foot above its deck. Twelve minutes after striking the vessel went down in about twelve fathoms of water. The boats made for the land, and arrived at the Yellow Patch light at about 11 o’clock. The light keeper directed them to the Cape Moreton lighthouse.

By Captain ALMOND : The chart he had was bought in Hamburg about three years ago. He bad not a large port chart on the ship. He provided charts himself. The chart he used was good along the coast. It was the chart of the east coast of Australia, and was the same that he used in going to Sydney. He navigated from Tasmania by this chart. He had a book of directions-" Findlay’s South Pacific Direc- tory." He took directions from that work. It mentioned Smith’s Rock and gave information as to where the pilot would come off. When the vessel struck hoe thought they were on Hutchinson’s Shoal. He never saw the pilot boat go out towards the ship. The pilot had told him that he did not leave the schooner until the rockets went up after the ship had struck. He saw no light on the water. The boat was seen by the lighthouse-keeper at the Cape. He saw the light of the pilot schooner as they were going towards the land. As he was standing in to the light he took the bearings from time to time from the lighthouse at the Cape. He thought, when he turned the vessel round to go out to sea, that the pilot schooner was about three or four miles away. He got signals from the light house; as soon as he showed a blue light the lighthouse burned a flare-up. The weather until they struck was fine, and there was little wind or sea. After- wards rain squalls were experienoed.

By the Superintendent of the Lighthouse: He first saw the Cape at about 4.30. They were then about sixteen miles off.’ It was a little hazy over the lighthouse. He was carrying full sail.

By Pilot BLANCHARD : He saw the sohooner’s flare-up as he went in. He did not steer for that, because that would have taken him inside danger. It was not usual for a vessel wanting a pilot to steer towards the flare-up. It was customary when a signal had been made for the pilot to coma out. If he had gone on among the rocks when he had signalled for the pilot and had lost his ship he would have been himself to blame, because he knew he had no right to do that. As a matter of fact he was in danger when he saw the schooner’s lights, but he did not know it.

By Mr, LEEPER: He did not succeed in saving the log-book or any memoranda from the wreck. On the day of the wreck it was too thick and hazy to get an observation, but the land could be seen plainly, and they bad to go by it. On sighting the first land he took a bearing, and from Mount Tempest took other bearings. When he saw Mount Tempest he could not see Cape Moreton, so that he oould not take a cross-bearing, which would have given his accurate position. The signals were answered from the lighthouse, but not from the pilot boat. Considering the state of the weather and sea he oertainly thought he could have been communicated with from the pilot boat. From the sailing directions in his possession he had not anticipated any difficulty in geting a pilot from Cape Moreton. He had a lookout from 6 o’clock until the ship struck. If a vessel had been cruising outside the Cape she would have been able to send a pilot on board in time to prevent the wreck. From the directions he had on leaving his port of departure he expected on arriving to be met by the pilot vessel or boat. His experience had been that the pilot boat should steer for the ship, not the ship for the pilot boat. His custom had been to heave to and wait for the pilot.

By Mr. FORREST : All he understood by seeing ! the flare-up from the cutter was that he had been Seen. He then expected that the boat would come off to him. By Captain ALMOND : The custom was that a vessel wanting a pilot, after seeing the signal from the pilot boat, steered for the latter, and the pilot boat steered so as to meet the vessel. Of course that rule was not fol- lowed if there was any danger between the ship , and the pilot schooner. When he first got a reply from the pilot schooner there was a danger between his vessel and the schooner - that was he thought there was. At this stage the inquiry was adjourned until 11 o’clock on the following morning. The Wesleyans have lost a well-known member of that body by the death of the Rev. John Wesley Close, whose death occurred at Bournemouth in his 60th year. For more than forty years he has been stationed in leading circuits. MAOUO CLIANSZR SOAP saves ooit of a washing boiler.

03 March 1894 - The Brisbane Courier - The Wreck of the Aarhus: Wreckage Washed Ashore #

The following article was from Trove’s archives6.

Some wreckage—believed to be portions of the ill-fated barque Aarhus—has washed ashore on Bribie Island and on the coast near the Maroochy River. From this many have concluded that the vessel is breaking up. The captain, however, maintains that no cargo could have come ashore; at most, a few deck-stores kept in a small deck-house may have found their way to the beach.

The inquiry into the circumstances attending the loss of the barque Aarhus was resumed yesterday morning before Captain T. M. Almond (chairman), the Hon. F. H. Hart, the Hon. F. R. Forrest, Captain R. S. Taylor, and Mr J. D. Campbell.

Mr A. Leeper (instructed by Messrs Unmack and Fox) appeared for the master of the Aarhus, while Mr Pietzcker, Danish Consul, was also present.

Mr Leeper renewed his application of the previous day that all witnesses be asked to withdraw. No charge, he argued, had been made against the pilot, the lighthouse-keeper, or anyone else, so they could not be treated as defendants. Citing section 7 of the Navigation Act 1871, he submitted that justice would not be served if witnesses heard the evidence of others.

The Chairman replied that he had received a communication from the master suggesting negligence on the part of the Moreton Island pilot and asking for an early inquiry; a direct charge therefore did appear to have been levelled at the pilot. The captain, he thought, alleged that the pilot’s neglect of duty led to the loss of the vessel.

Mr Unmack contended that the Marine Board was not the proper tribunal—an executive inquiry, he said, would be more fitting—and that witnesses should be excluded when evidence was taken. One deck officer had already been asked to withdraw; the others, he argued, should receive the same treatment.

Mr Pietzcker observed that he had sought the inquiry merely to ascertain the facts, not to accuse anyone.

The Hon. F. R. Forrest, taking his seat, considered there was no need for witnesses to remain: the object was simply to discover the facts. The Chairman accepted the explanation and ordered the witnesses to retire.

Mr Leeper then asked that Captain Almond withdraw, as he might later have to report upon his own departmental officers. The Chairman declined, explaining that the men were officers of the Marine Department, receiving instructions from the departmental secretary, not from him personally.

Mr Leeper asked that his application be noted.

The Chairman replied: “Certainly not; I refuse the request.”

Mr Leeper argued that because the departmental officers were not implicated, the chairman could not be called upon to report on their conduct. Mr Forrest suggested that if the point applied to the chairman it applied equally to every member of the Board. Mr Unmack added that Captain Almond held a dual office—Portmaster as well as Chairman—and was thus already part of the department in question. Mr Forrest pointed out that the harbour-master, not the chairman, had immediate charge of the staff.

Resuming, Captain Gram said the statement he made the previous day—that at 7 p.m. the ship was ten or fifteen miles off the land, steering N.E. by E.—was incorrect. He had misjudged the distance because of fires ashore; in truth they could not have been more than six miles from land. Later events showed that Cape Moreton did not in fact bear W. four miles, as he had supposed at 8 p.m. From about 7.20 p.m. until the vessel struck, the second mate had the deck, and they believed they were still four miles west of the cape.

The mate thought they were five or six miles from the cape at 8 p.m.; subsequent events proved they were probably within one mile. Heat haze made distances hard to judge. At the time he altered course, Captain Gram believed he was clear of danger.

Coming up the coast the officers had carefully marked the position of Smith’s Rock on the chart. Directions said the danger was buoyed with a black buoy and staff; they were looking for it but did not sight it. They afterwards discovered the original buoy had been washed away in a gale and replaced temporarily by a much smaller one.

Questioned by the Hon. F. R. Forrest. —When Captain Gram saw the pilot cutter he was not afraid to run in, but thought he was already outside the rocks and that going in was unsafe. He noticed a barque at anchor, yet it never occurred to him that he might anchor safely near her. Directions stated that the pilot would come out, so he felt no need to approach the schooner.

By the Chairman. —Had he seen the Yellow Patch light, he would have known he was inside the rocks; because the light was invisible he assumed himself outside. His outbound bearing was S. by W. ½ W. He now realised that had he held that course, instead of altering to N.E. by N., he would have been safe. He first saw Yellow Patch light only after an hour in the boat.

By Mr Campbell. —The distances he gave yesterday seemed correct at the time, but the wreck’s actual position proved otherwise. He still believed the pilot schooner could have reached the Aarhus before she struck, even on yesterday’s distances.

By the Chairman. —The Aarhus was insured, and underwriters expect vessels to carry proper charts; he had charts for the whole coast round to Fremantle.

By Mr Isitt. —At other ports it is usual for the pilot boat to come out to the ship, not vice-versa.

Hans B. O. Corser, chief officer, said he lost his certificate with the ship. He had served twenty-three months in the Aarhus and had signed the crew’s written statement after reading it carefully, though he doubted the bearings. Noon sights on Saturday were taken in hazy weather; the statement’s distances afterwards proved too great. They never succeeded in taking cross-bearings and never sighted Yellow Patch light.

Julius Severinsen, helmsman, took the wheel at 3 p.m., steering S. by W. ½ W. After a quarter-hour the captain ordered him one point east. Cape Moreton light was then on the port quarter. He was still at the wheel when the vessel struck.

Hans Jensen, ordinary seaman, was on lookout on the forecastle. He saw three lights—two on the pilot schooner and Cape Moreton light—but could not recall how many rockets were fired.

Peter Nold, on watch when the ship passed Cape Moreton, stated he fired all twelve rockets after she struck. Only ten minutes elapsed between the impact and abandoning ship; he could easily fire a dozen rockets in that time, holding them while Captain Gram applied the port-fires.

The inquiry was then adjourned until 9 a.m. on Monday.

Letter to the Editor

To the Editor of “The Courier.”

Sir,—In 1850 a German vessel—her name escapes me—left Moreton Bay for Sydney and, on the passage out, scraped a rock lying nearly midway between Cape Moreton and Flinders Rock, though she suffered no damage. She reported the incident at Sydney, but the authorities ignored it, Moreton Bay then being of little account to them. Long before this, masters of coasting vessels had noticed a break in the sea there during heavy weather and always gave the spot a wide berth, uncertain of the depth.

I was one of them. On one occasion, my vessel drawing only eight feet, I tried to cross the patch at high-water to take soundings. Only one chart—Captain Whitelham’s—then existed, so I guessed the position; the shallowest water I found was four fathoms, and that on a single cast of the lead.

In 1858, while H.M.S. Herald (Captain Denham) was surveying outside the banks, Lieutenant Smith discovered the rock, which now bears his name. Captain Denham recommended buoying it; a bell-buoy was sent from Sydney, but the bell was too feeble and the buoy unsuited to heavy seas, disappearing in the first blow. When I laid it, the water was smooth and clear—I could see the rock’s crest. It is small and fissured, and I have long thought that one or two charges of dynamite might remove the top, adding a few feet of depth. That would lessen the danger to shallow-draught craft, though shoal water would still surround it.

The winter months, with their calmer weather, would be an opportune time for an expert examination to see whether this could be done.

I am, sir, &c.,

H. W. Wyborn

-

The Wreck of the Aarhus, The Brisbane Courier, 02 March 1894, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3575323 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Maritime Archaeological Association of Queensland. (1989). Aarhus wreck site: A report by the Maritime Archaeological Association of Queensland. Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology, 13(1), 9–14 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Queensland Government, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection. (n.d.). Dive into history – Queensland’s shipwrecks: Aarhus (1894) (Brochure). Queensland Government, https://www.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/67424/dive-qld-shipwreck-aarhus.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Queensland shipwrecks expose their secrets, Brisbane Times, 20 November 2011 https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/queensland-shipwrecks-expose-their-secrets-20111118-1nnd4.html ↩︎

-

Undersea Productions, Aarhus shipwreck: ‘Ocean scenery on deep historic collapsed wreckage’, https://media.underseaproductions.com/img/22/22793.jpg ↩︎

-

The Wreck of the Aarhus: Wreckage Washed Ashore, The Brisbane Courier, 03 March 1894, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3575386 ↩︎